Every writer has a quick answer for, “What do you write?” For me, it never feels quick or easy. I have an elevator pitch, just like the next guy, but it always gets a follow-up, no matter how concise I make it. A typical conversation goes like this…

“What do you write?”

“Crime thrillers.”

“Oh, you mean like police and detectives?”

“Not exactly. I write in a sub-genre called crime noir.”

“Huh…”

I can see the wheels turning as that lands before I hear, “You mean like the old black-and-white movies? All smokey and dark?”

“Kind of,” I say. “But more modern. They call it neo-noir?”

And from there, I’ve either lost them completely, or they’re afraid to ask what neo-noir is all about. So I developed the short version.

“I write crime stories where everyone will have a very bad day.”

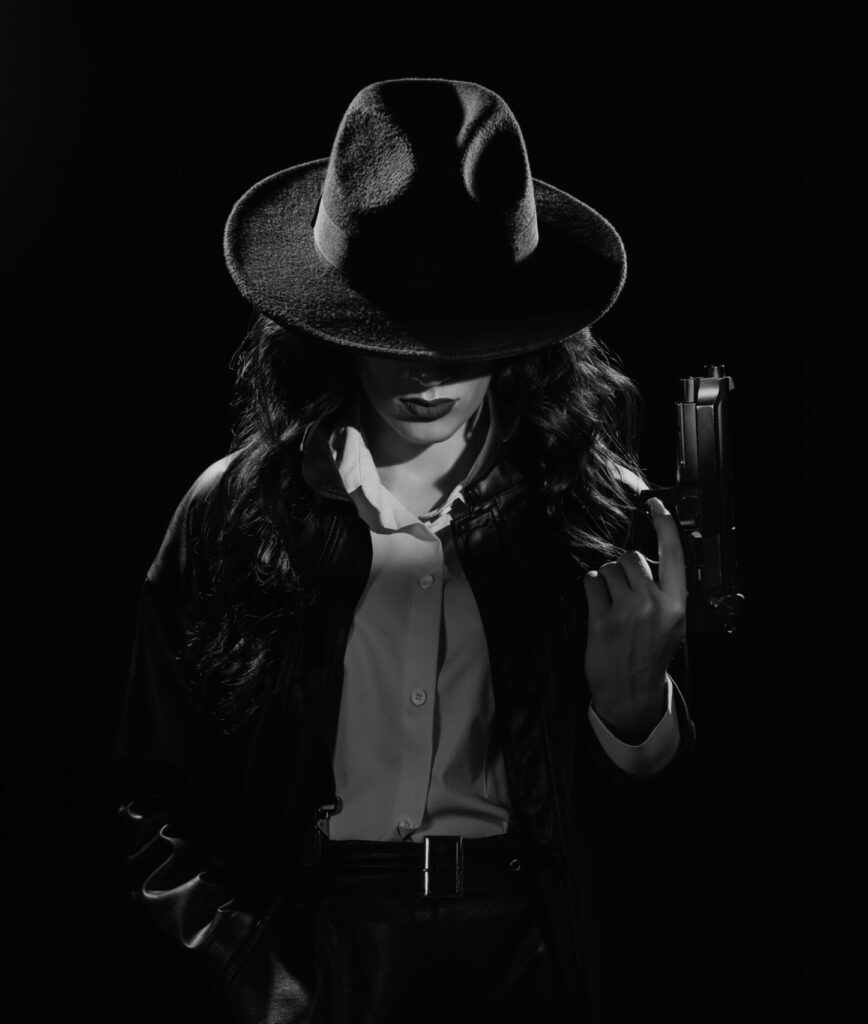

Pretty dark and fatalistic, wouldn’t you say? And that is exactly my point. Neo noir, at its essence, is still the dark story it was when it showed up in the late 1920s, but with a few twists. It has all the delicious elements of the well-known format, but we’ve put a spin on it, and we continue to refine it with every new story.

So yes, it’s often described as dark and “gritty,” which is polite code for the realistic bits that are only implied in more traditional thrillers. You may read a review with vocabulary like bleak, menacing, deviant, hard-boiled, and with characters that are morally compromised. Yes, yes, and yes. Noir and neo-noir share all of those characteristics and more. But it’s the subtlety of refinement over the decades that fascinates me.

It’s no secret most noir appears to be written by men, for men. We’ve all seen the iconic covers that define the history of noir and the perceived threat of post WWll gender roles. (And if that’s new to you, treat yourself and read more about the history. Crime Reads has a couple of great articles you can find here.) But women write some of the best noir, then and now.

Today, noir could just as easily have a woman as the main character. She may still be the femme fatale you’re used to (or not) but she’s just as likely to be the head of a crime syndicate. From Patricia Highsmith and Dorothy B. Hughes, to more contemporary noir writers like Megan Abbott, women continue to make noir their genre of choice.

That’s just one of the ways it’s changed over the years. A friend of mine recently asked what made a book noir? At what point does it cross from being a good psychological thriller to noir? There are a lot of brilliant answers, but I think of it in some pretty broad categories.

- First, noir crime fiction is both thriller and noir. It’s not either/or.

- Noir will focus on the criminal, not the police, the detective, or the amateur sleuth trying to solve the crime. The actual crime is where we want your attention, so the character driving the plot is never the good guy.

- A good noir won’t explain the moral dilemma. It’s going to make you live it along with the character.

- As the lyrics by Cage the Elephant will confirm, “There ain’t no rest for the wicked until we close our eyes for good.” Our characters have an emotionally and physically exhausting dilemma. The only question is, how far are they willing to go to end it?

- Good noir will fuse the moral questions of a story and plot so tightly, the jaws of life are about as effective as your kitchen can opener. You may even sympathize with characters who are shades of evil, but never fully innocent. Never.

- This one is my personal preference—location is crucial for me. If it’s a setting with some rough edges, rather than polished glass and steel, the story immediately sets a tone. Not to say noir can’t take place in your local HOA among the spring tulips. Sure, it could happen, but if the character is in a rough environment with limited resources, they’re running out of options and it immediately sets the mood. I think we can all agree, a character who’s out of options is infinitely more interesting and likely to do something morally ambiguous.Take these more contemporary titles that hint at some sketchy locations—Blacktop Jungle, by S.A. Cosby, Ozark Dogs, by Eli Cranor, and Notes On An Execution, by Danya Kukafka. Each one instantly cements a darker expectation than pure thriller.

That’s part of my own criteria. I won’t presume to list other writers’ preferences, or their many views of how noir will evolve, especially for women writers. It’s all fluid. What I can promise is noir authors will always invite you to take a walk with them and share a psychologically intense story with brutal honesty.

The second question someone asks me is, why? Why did I choose to write the dark stuff?

Raised in the idyllic world of Leave It To Beaver after school, and the Night Stalker after dark, the 60s and 70s shaped what I read, and later, what I would write. I lived in two worlds, on a steady rotation of Catholic school catechism during the day, and the best smoke-filled thrillers late night TV had to offer. There was impunity for vicariously living on the streets and in back rooms of everything morally questionable.

The contrast between worlds, however, was an eye-opener. There were shades of gray I probably wasn’t supposed to understand for years, but the stories entice you in, inviting you closer. It didn’t take long to understand things aren’t always as they seem. And that is where the real story lives.

Intoxicating stuff for a future writer.